How Companies Can Deal With Rampant Digital Ad Fraud - Forbes

DECEMBER 17th 2020: Ten states have filed a new antitrust lawsuit against Facebook, Inc. and Google ... [+]

zz/STRF/STAR MAX/IPxby Erik Sherman

When 19th century retailer John Wanamaker famously said that half of his advertising was wasted but he didn't know which half, he was talking about effectiveness.

These days, many marketers could say half their marketing dollars were wasted even before anyone had a chance to see them.

Online advertising has developed a terrible reputation for good reasons. Fraud and waste burn through billions a year in wasted investment. Corporations are wondering how to make their ads pay off. The answer is with difficulty.

Layers of technology intended to create unwarranted advertising spending combine with byzantine labyrinths of service providers that are huge expenses for advertisers and publishers alike.

On the advertisers' side, outright fraud is huge in scale, with an array of technologies intended to create false ad impressions, which advertisers pay for even though they get nothing from it.

Ads knock, nobody is there The fraudulent techniques include overseas click farms paying people to repeatedly click on ads, software bots that pretend to be consumers, and large numbers of ads jammed onto fly-by-night webpages to maximize charges. "Using all manner of data, people using fake bots, fake websites, fake attributions—[the fraud is] on the order of $30 billion annually," said Roberto Cavazos, director or risk management and cybersecurity programs in the Merrick School of Business at the University of Baltimore.

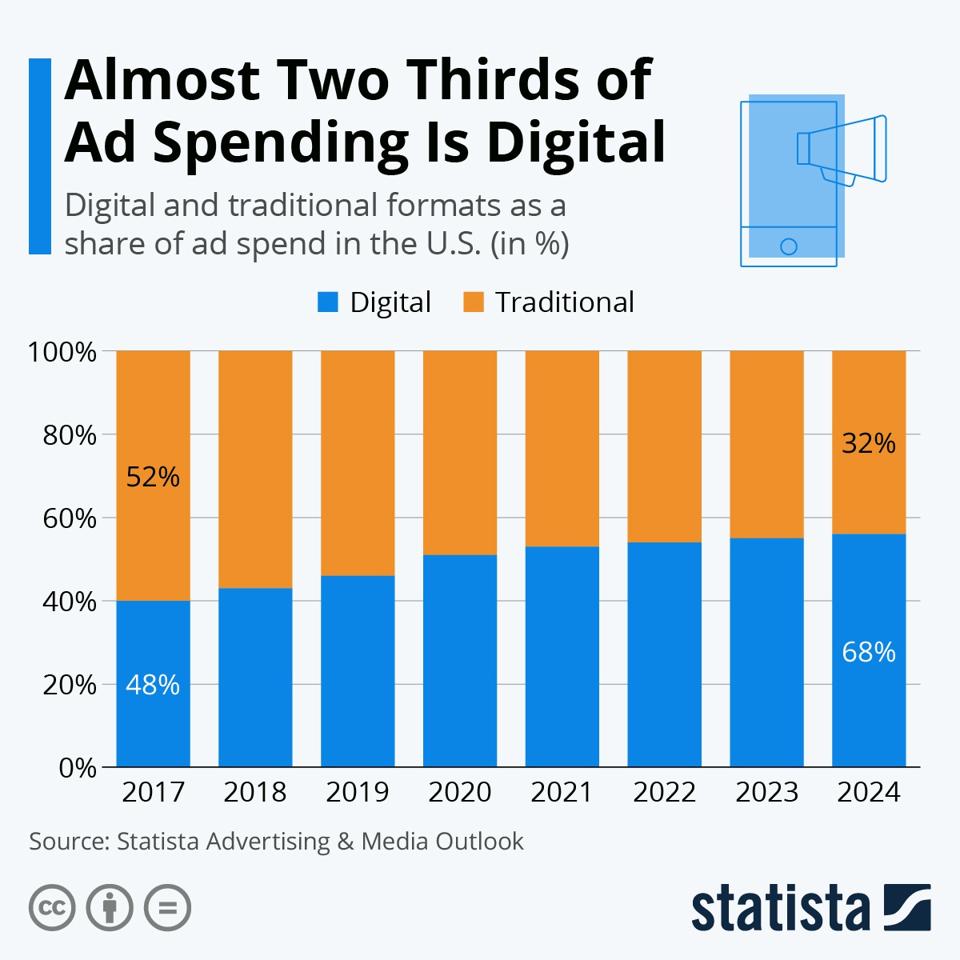

Digital ads continue leading in advertising revenue.

StatistaMORE FOR YOU

Over the last few years, some big business names experimented, cutting back on digital ads to see what happened. Proctor & Gamble spent nothing on digital ads one year to see what happened. "They didn't miss any sales," Cavazos said. "There's a lot of big players that have a sense things are not right."

"I would say advertisers who are funding this system aren't the only victims," said Keri Bruce, a partner at law firm Reed Smith. "The publishers are victims here too because they're not getting all of the dollars they should be getting."

Uber filed a lawsuit in 2017, alleging that Phunware and Fetch Media, Ltd. had committed fraud in their handling of the company's dgital advertising and eventually settled for $4.5 million, according to a settlement agreement filed with the SEC.

Smaller companies can't necessarily use the same tactics.

"If I'm Caterpillar tractors, I'm not that worried about it," Cavazos said. "If I lose money in ads, I make it up in a couple of D10 [tractors]. If I'm a consumer or a group of small businesses, I'm advertising my hair solons or chain of pizza restaurants, and my revenue is $8 million a year and I lose a couple of hundred thousand, it hurts."

What you don't know hurts you

Then there's the complexity of the system, which not only makes it difficult to fight fraud, but also to control ad spend.

Companies must keep track of online advertising or they may be defrauded.

getty"I have really sophisticated clients in this space and a lot of less sophisticated clients," said Bruce. "There are bigger brands with bigger dollars, bigger teams, analysts inside, and they have really experienced people who know this stuff and get into the data and [know something is wrong]. Then you have brands who outsource everything to their [ad] agency because they can't afford to have these teams in-house and they don't have the experience."

Even when a company does have the resources and access to the data, it can take months to track down problems. The implications are even worse for small businesses.

"It's a dilemma for small businesses with limited resources," said Heather Jiang, co-founder of sustainable fashion startup Allégorie. "The ad results from these platforms are not linear to the money invested. It's more of a winner-takes-all situation where big spenders enjoy almost all of the traffic." Those with resources can bid higher in automated auctions for ad space and block out less well-funded competitors.

The prices have been rising rapidly. Evan McCarthy is CEO of SportingSmiles.com, an online seller of custom dental products with 12 full-time employees and three part-time ones. He spends 22% of gross revenue on digital advertising. The numbers rarely add up.

"If I took all the platforms and added up how many conversions they say I got from their platform, I'd bet it's 30% higher than what the true number is," McCarthy said. "Everyone inflates the value."

The costs are significant, even on a per-lead basis. "At one point I was pumping out a ton of leads for $100 a lead," said Doug Hentges, founder of DH Home Solutions, a local home buying company in Dallas-Fort Worth. "Now I'm paying anywhere from $250 to $300 for a single lead. I'm paying $20 to $75 for a single click. People think they can come in an compete and put up some ads. You just can't do it anymore."

Ad delivery also involves complex supply chains. A single online ad placement can ultimately involve 20 different players, according to Cavazos. "The ecosystem for online advertising is complex, and I would even argue unnecessarily so. Anything you add complexity to, you're going to add waste and costs. It's like a 15% tax on every dollar."

"The advertiser does not have a relationship with the publisher at all," said Rajiv Khaneja, a serial entrepreneur and founder of ad tech companies AdButler. "Just like a fisherman on the boat doesn't have a relationship with the person who buys the fish." Consumers at a market have no idea whether the fish they purchase is actually what the seller claims. And the seller depends on a wholesaler, who may get it at a commercial market, where a distributor bought it from the boat.

Online advertising is a good way for some companies to reach customers, but companies need to keep ... [+]

getty"As more and more advertising moves to programmatic [automated systems of ad placement], where you have more players in the supply chain, you have more people along the way with incentive to commit fraud some way," Khaneja said. "You're far less likely to be caught. Everyone points the finger at everyone else and no one gets into difficulty."

Ruthless action

One step a company can take to reduce the problem is to focus on sensible results and drive that orientation through the organization. For example, demanding impressions alone is a sure way to waste money.

"I used to joke I just want a client that wants to get me impressions," said digital advertising consultant Matt Lally. "That would be the easiest thing. "But there are [agencies and clients] where the marketing manager isn't so concerned about performance. They want to use out their budgets. They say to their agency go out and spend this. Get me as many impressions as they can. Some are trying to hit markets for their boss's boss."

Companies have to be ruthless about what they demand. "If you can't see conversions in your Shopify store or you sales team is saying these leads are crap, you should cut the source" Lally said. "Even if I'm working with a brand and half of the inventory is fraudulent and I'm still hitting the metrics, how can I cut away the fat?"

That's assuming the company wants to remove the bloat.

"CMOs have a big job," Bruce said. "They don't get paid for fighting fraud and waste. They're paid for performance. If sales are going up and if whatever your KPIs are for a brand are improving, then what incentive to brands have to take a closer look at the waste?"

But that can be a dangerous position. When it comes to advertising, the real products to the ad ecosystem are the advertisers.

"Facebook and Google are machines designed to suck money," said Mike Koehler, founder of Smirk New Media, a digital marketing agency based in Oklahoma City. "They want you to run the ad as long as you can. If they set up an ad campaign and then walk away and wait for results, that ad is going to spend and spend and spend, regardless of whether it's getting any results."

Comments

Post a Comment